I want to let you know that this isn’t our usual blog post where we share photos of pretty cocktails, beautiful meals or our once-in-a-lifetime unique COVID experiences. This blog pertains to the first half of our month-long trip in Ethiopia — visiting the ancient tribes of the Omo Valley.

When Scott suggested that we go to this off-the-grid country, I didn’t know what to expect. The one or two documentaries I had watched years ago about tribal living certainly didn’t prepare me.

I didn’t understand that while visiting each tribe, we would be sitting in their huts, attending their most important ceremonial rituals and talking with the children and family members about their day-to-day lives. And I certainly didn’t expect the emotional impact this experience would have on me.

Without a doubt this is the most challenging blog post I’ve written.

To set the tone:

Grab an Ethiopian beer (St. George or equivalent),

Turn on Spotify‘s Traditional Ethiopian Instrumental Channel with Mesele Asmamaw (the music we listened to during our daily road trips)

Now let’s dive in.

SOUTHERN ETHIOPIA

THE OMO VALLEY

Arba Minch, Konso, Turmi, Omorate, Jinka

February 25th - March 9th, 2021

THIS ONE

Me and Arsema

As soon as I got out the the truck, this little darling latched on to my hand and wouldn’t let go. She looked at me and I looked at her and off we went to visit her people of the Karo Tribe.

We spent the morning walking around her village, located on a ridge above the Omo River.

At times she held on to me so tightly that I had to shake her loose to take pictures and talk with the other children. But she never left my side.

As we sat in one of the huts chatting with a local family, pretending to drink coffee from a gourd (a mix of hot brown river water steeped with coffee husks), I removed my hat and she and I played hide and seek. She giggled constantly — my little spark of sunshine.

Her name is Arsema Kale. I guessed that she was 5 or 6 years old — though tribal people don’t actually track age so it’s hard to know for sure.

There was something about her, I couldn’t say what. We had visited many other tribes before hers and held many other hands, but she was different.

Before Scott and I left that day I gave her a small string bracelet with a gold circle that I purchased for myself in Istanbul.

She had won my heart.

WHY ETHIOPIA?

Realize that most people who visit Ethiopia, go for an experiential trip (not a typical vacation) — intrepid travelers, photographers, missionaries and members of the United Nations. We were none of these. Just curious human beings exploring the world.

Scott’s friend, Bruce Stanley, was the only person I knew of who had traveled to Ethiopia. He suggested that it was “a truly unique experience.”

An understatement I would later discover.

But, as I am prone to respond repeatedly on this adventure, I quickly said, “Yes!” when asked if I wanted to go.

Bruce also suggested that we hire Fitsum Ashebir, owner of Omo Valley Tours, to be our guide. It’s pretty much a requirement to hire a guide while traveling here, and Fitsum was awesome (more on him later).

Scott and our guide, Fitsum Ashebir

OUR JOURNEY BEGINS

Our hipster driver, Isreal Legesse

From Cairo, we flew into Addis Ababa and stayed one night. At six the next morning we jumped in our Toyota Land Cruiser with our driverIsrael Legesse and Fitsum and headed out on a day-long drive south towards Arba Minch to start our journey.

When we asked our new team how long our drive would be that day they said seven or eight hours — it took twelve.

That was when we first discovered that Ethiopian time was quite different than our own.

The road conditions were brutal. Cattle finally let us pass.

This road was the main connector for everything from people and livestock to water transportation. When we stopped to take pictures of the cattle, these lovely ladies invited us into their hut nearby for coffee. Inside we were introduced to our first peek into another world.

Our delightful view of the bush.

ARBA MINCH

When we finally arrived at the Haile Resort in Arba Minch that evening, we were sweaty and road-worn. The daytime temperatures were hovering around 100 degrees. And, you guessed it, no AC in our truck.

We thought there had been a mistake.

We’re on a budget trip but we had pulled up to a luxury resort. Fitsum assured us we were in the right place. It was beyond a welcome relief — air conditioning, wifi and a shower awaited us.

Scott and I enjoyed a nice meal on the terrace overlooking Nechisar National Park and Lake Chamo. It looked like a good place to swim. Later we found out that the lake is infested with crocodiles.

Welcome to Africa!

We took the next day off to recover from our road trip and to prepare ourselves for the next 25 days.

The sunrise that next morning over the distant mountain range was beyond a dream. It made me want to paint a picture because no photo would capture the beauty we were seeing.

THIS IS BREAKFAST?

Our first stop heading out of town was touted as a gourmet breakfast. I’m not sure how we got talked into this but Fitsum introduced us to this special Ethiopian delicacy — freshly butchered raw meat (and no I’m not talking steak tartare) — usually from a cow, and sometimes a goat. He described this as “date food” since meat here is very expensive and you’d be impressing your date with a splurge like this.

Since the animal is butchered early in the morning and the meat is best eaten fresh, breakfast is the ideal time to indulge. I had a hard time wrapping my head around this.

Walking into this crowded restaurant first thing in the morning was a bit of a shock, but not as much as seeing “breakfast” show up at our table. The platter looked like something you’d prepare to take to your grill.

Scott managed to eat his share, but I politely declined.

THE TRIP AHEAD

Our plan was to visit eight or nine different tribes over the next couple of weeks. This would allow us to understand the similarities and differences of these tribes and their customs.

Many of our visits were planned so that we would arrive in their village at dawn so we could meet as many people as possible before the tribal men left to farm or herd livestock that day — and to take advantage of the coolest part of the day. We often drove an hour or more over long gravel roads into these extremely remote locations.

Fitsum would also hire local tribal guides to join us to introduce us personally to the tribal members and to show us around the villages.

Scott and I settled into the back seat of our Land Cruiser with Fitsum and Israel in the front. This bumpy and dusty hot view would be our vantage point to this part of the world for the next twelve days.

Beads, pineapples, goats, cattle, people, potholes and 100 degree temperatures are the best ways to describe our daily travels on these dusty roads through the Omo Valley.

LIFE IN THE OMO VALLEY

Let me see if I can properly paint the picture…

Tribes have lived along the Omo River for thousands of years. Archeologists even found a jawbone here from ancient man dating back 2.5 million years ago! It’s shocking because life is so challenging here. Know that back then when mankind settled in this region it was much greener and lush. Now it’s not.

Also, many of the tribes were nomadic — moving with the seasons, to wherever there was adequate food and water. Now, tribes have grown and expanded to reach their borders keeping them in place, and local resources are much more limited.

THE ROADS

The roads we encountered varied. Close to the cities we had decent paved roads but as soon as we turned off the main highway, gravel and potholes were the norm. We often drove in the ditch alongside the road because it was a smoother ride. The combination of road dust and our own sweat mixed with the heat of the day added another layer to our adventure.

LANGUAGE

There are more than 120 different languages throughout Ethiopia and each tribe has a slightly unique dialect. There are no written languages for these tribes, only spoken words. Very few people speak English.

TRANSPORTATION

Walking or riding donkeys are the main modes of transportation in this area — though we did see a few tribal members on motorcycles.

WEATHER

A very dry hot 100 degrees every day with almost no shade.

Rainfall can accumulate to as much as 40 inches per year, however, it tends to come in torrential rains and then is dry for much of the remainder of the year.

HOUSING

Many huts are constructed to resemble animals. This one is an elephant.

Most people live in huts — some more beautiful than others. Some round, and the more modern homes are square. Regardless of shape, they are all built with the same locally sourced building materials: eucalyptus tree limbs, mud and straw walls, thatched or tin roofs and dirt floors.

UTILITIES

No running water. No electricity. No plumbing.

There are very little resources here. In the cities, more so, but not in the remote tribal areas.

Termites are a huge issue in this area and the locals have learned to build to accommodate their appetite by building very tall huts. They just keep adjusting the door heights as the huts get shorter.

We were able to get limited cell service in some areas near town and along the paved highways.

WATER

Water is a big issue here with the tribes throughout the Omo Valley. Some say it’s the biggest single issue they deal with — with the threat of COVID being a non-issue.

There are two rainy seasons every year. A short season in April with the more intense rainfall in September/October.

With no infrastructure, water must be collected from the river or harvested from dry creek beds by digging down to find ground water. It is then filled into yellow containers and transported to the villages strapped on the backs of women and children or carted in on donkeys.

They drink this water unfiltered, straight from the container it was collected in.

FOOD

Doing some Saturday market trading

They primarily farm. Their main food sources are grains like kir and sorghum and, on special occasions, goat, beef and even camel. They trade what they don’t consume at the weekly markets.

The cattle graze on anything green, which is extremely limited during dry months — and most months are dry.

There is no irrigation, so only rain water sustains plant growth.

MONEY

A barter system is in place — currency is in the form of cattle and goats. The limited cash that does come into these tribes usually comes from tourists.

As tourists, cash is king and credit cards are rarely accepted anywhere. We were surprised to know that ATMs weren’t that hard to find.

EDUCATION

Only 1% of tribal children attend school. This is due to the lack of available transportation and the long distances to the nearest schools. But also, tribal parents discourage formal education because they know that everyone is needed to help sustain life here — to herd livestock, transport water, cook, and help raise the children. It requires a team effort to stay alive.

They also know that children who get an education tend to leave their tribe.

HEALTHCARE

Most tribes do not have access to medical care unless missionaries or humanitarian organizations provide this service, and typically they focus on child birth and communicable diseases.

Anyone who is sick or wounded goes to a tribal healer for blessings and ointments. Honey, tree sap and prayer are the typical remedies used.

Life expectancy is around 50 years old.

THE PEOPLE

TRIBAL MEN

Yep, those are goat intestines laid out on a gourd. The elders are reading the “signs” and advising the man in the striped serape (lower left) about whether he had been cursed.

The men we met all seemed to have similar traits.

They are the known protectors of their villages. As well as mediators to help settle conflicts between families or other villages. They also focus on the markets where they buy and sell their animals.

We often didn’t see many men around the villages, and were told that they were out with the cattle or working in the fields.

Often you would see men holding a rifle or a finely sharpened stick — a symbol of power and authority. Fitsum assured us that, more than likely, these guns had no ammunition and likely posed no threat.

The elders, on the other hand, seemed to spend their time wandering around the camp, not in a hurry to do much. They were often grouped together discussing deep issues — we didn’t really find out what — or playing board games.

TRIBAL WOMEN

The roles and rituals of the girls and women seemed far more vast and harsh.

From the age of 4 or 5, little girls learn to take care of their younger siblings. They wrap them on their backs and keep them busy while their mothers prepare food for the families. They only take them back to their mommas during the day to nap and nurse.

In general, tribal women typically have 5 to 15 children, which means they are breastfeeding for the better part of 10 to 20 years. And still, tribal women perform the majority of the work around the village.

They haul water, grind grains, farm and are required to keep a fire burning in their home day and night so that it’s possible for them to make a meal or fix coffee for men returning from herding or market trading.

TRIBAL CHILDREN

These babies!

So sweet. Happy. Full of life. Playful and carefree.

They loved us. Our light skin. My blonde highlights. Our blue eyes. Scott’s gold fillings. His sunglasses. Our clothing. Everything about us was unique to them and they wanted to know more.

Our iPhones were a great way to connect. They were mesmerized by seeing pictures of themselves and they loved getting our attention.

We didn’t walk anywhere that we didn’t have a large group of children around us — both hands busy with little ones attached.

THE TRIBES WE VISITED

THE DORZE

Our first stop was to visit the Dorze tribe. They build the most amazing huts and are known as master weavers.

We enjoyed a trip through their local Saturday market and totally stood out. Children followed us as we walked through the rows of vendors — the adults looked at us with total skepticism.

We visited their tourist village where we were able to tour the interior of one of the huts, to try my hand at weaving, and we even sampled some local moonshine. They were obviously accustomed to hosting tourists, showing off their best talents by performing some of their traditional songs and dances.

Just down the road we met with the ambitious Konso tribe.

THE KONSO

Taking advantage of the hilly terrain, the Konso’s discovered the best way to farm this land was on terraces. For miles we saw these terraced landscapes.

Terraced Konso Tribe land

The Konso are considered one of the hardest working tribes in the Omo Valley - with some very talented masons. Many of these dry laid walls have stood for thousands of years.

Their village was one of the prettiest we visited. Shaded by beautiful Oak trees, each home had very neatly kept dirt yards surrounded by artfully arranged dead wood branch fencing.

We also discovered that the Konso people were very creative. As we walked through their village we marveled at their artwork, jewelry, handmade soaps, and wood carvings and structures.

We enjoyed giving pens to the kids — which they happily snatched from our hands.

Check out Barak Obama’s picture on the box. How random is that?

THE DASSENCH

As we drove up to the village, we noticed a lot of naked, barefoot children running around kicking a wad of paper through the dirt as if it was a soccer ball. I was surprised by how many children there were.

And as we got out of the car, Fitsum casually told us that this tribe practices “Dimi” (female castration). From some National Geographic documentaries I watched years ago I understood that some tribes still practiced this ritual, however, I didn’t think we’d actually visit any who do.

And even through I heard Fitsum’s words, I quickly blocked them out of my head and immersed myself in the busyness of the visit.

The Dassench are located in the hottest region of the Omo Valley. Their huts are covered with scrappy pieces of tin sheeting to reflect the effects of the harsh sun. The area around the huts was barren with the exception of animal dung everywhere.

They are one of the last nomadic tribes in the valley. It is now very hard for them to survive as they can not move around to find better access to food and water.

They also do not have an established system of farming. The Ethiopian government has sent people to help teach them, but as we walked around, we could tell that they were struggling to provide basic resources.

My “Angelina Jolie” moment. I totally get her now. I wanted to take all of these babies home.

THE HAMER: PART 1

Introduction to Hamer Life

The Hamer Tribe is largest tribe in this area around Turmi — about 50,000 members. And there are many Hamer villages spread out over this large area.

As we entered this first Hamer village, we noticed how clean and organized their huts and yards were — certainly compared to the Dassench. No trash or animal waste anywhere. All was swept clean.

They welcomed us warmly into their village and a local family invited us into their hut for coffee. It’s customary to share a meal or beverage — or anything you have — with your guests, whether you have enough for yourself or not. No one will leave without a little something in their tummy.

And of course, we couldn’t walk five feet without a young child grabbing onto our hand.

I couldn’t help but notice the blank stares from these tribal women.

THE HAMER: PART 2

Marriage Ceremony

Fitsum told us that we were lucky to be visiting on this day — that we could attend an important ceremony — the ceremony celebrating trading a young Hamer women to another tribe to be married. Since he called it a “celebration,” I thought “Oh OK, this should be fun.”

The celebration started at sunset, but we arrived earlier that day to walk around and meet some of the locals before the festivities began.

You could tell there was a buzz in the air. Children running around. Women preparing food and drinks. Young boys bringing their goat herds in for the night. Other tribes arriving on foot from the nearby villages.

As the sun began to set, we walked by one of the huts where the bride-to-be was living. We got close enough to hear her wailing. Not sobbing or crying, but wailing. It honestly didn’t sound human.

As darkness fell, she was coaxed out of her hut by her family and female tribe members. Arms around her, they transported her lifeless body as they chanted their support. We quickly understood that everyone but the bride was celebrating — as the tribe gains about 40 cows in trade.

They moved her to an open area nearby that was completely covered in sheets of cardboard, and then came to a seated circle where their supportive chanting continued.

The locals and visitors came to her with kinds words and cash to send her on her transformative journey.

The bride has the white blanket around her shoulders.

We left after a couple of hours of chanting, but were told that this would continue throughout the night. At sunrise, the family and tribe members would walk the young woman to her new village — never to see her again.

THE HAMER: PART 3

Bull Jumping Ceremony

On the next day, Fitsum informed us that we were again lucky to be in this area at this time. A rare bull jumping ceremony was on the agenda for the day.

I thought, “OK, surely we won’t see any traumatized women today.”

This is a huge event in a tribe and certainly in a young man’s life (in this case, he was the chief’s 18-year-old son).

This coming-of-age ceremony will determine whether he becomes a man, can marry and have children. Or will he be shamed?

This ritual involves him running naked across the backs of ten bulls being held by other tribesmen. He must run back and forth and not fall.

And if he makes it, he passes his test.

This is a huge event for the tribe with so much preparation. Other tribes come from miles around to witness this event.

The entire village was alive — singing, dancing and cheering.

But there was another part of the ceremony that I wasn’t prepared for — the whipping ceremony.

For women, this is where they prove their bravery and worthiness to their tribe. Fitsum told us that the motivation of these women is to show the men of their tribe what they were willing to endure — by doing so, the men are forever obligated to protect them.

WTF?

Yes, we witnessed this whipping.

Old and new wounds are shown proudly

Now in my own strange fascination and WTF reasoning I said…”OK, if we’re going to see this, I want to know…Are they forced into this (surely they are because who would ask to be whipped)? How do they withstand the pain? And who the hell came up with this idea?”

The women, quite frankly, look the whipper (the Maza) straight in the eyes and beg to be whipped!

This all happens after each woman has spent the morning gathering and preparing 4 or 5 of her own whipping branches, stripping them down into long pliable whips. Then a large group of thirty or so females gather to support each other in a dancing frenzy — chanting, laughing and drinking fermented sorghum in the hot desert heat.

When the dancing slows down, they circle around the whipper and taunt him, saying things like “Prove you’re a man,” “I love you, whip me harder!”

When he whips them the women never blink and their smiles never leave their faces.

The dancing and whipping continues through several rotations over the course of a 24-hour period until the women’s backs are bloodied to their satisfaction (that said, they wear bras to protect their breasts). This continues until the women run out of whips or the Maza gets tired and refuses to go on.

After spending ten hours that day in the hot sun, experiencing all that we had experienced, we shuffled back to our truck and drove back to our lodge.

I was totally numb.

THE ARBORE

It took us several hours to get to the Arbore Tribe. Being off the beaten path, this tribe doesn’t receive a lot of visitors.

The Arbore are known for their bead work, which they proudly display around their necks and wrists. Each piece of art represents their talent and wealth.

As we approached, Israel honked the horn and the children came running. Everyone seemed happy to see us.

And as we got out of the truck, Fitsum mentioned that this is another tribe that performs Dimi.

Shit!!! Really? Another tribe?!

After a brief tour of the village, we were invited into a hut and treated to some hot coffee (which we pretended to drink) — and were soon joined by a couple of tribal elders.

I was surprised when the conversation turned to Dimi.

One of the Arbore women sipping coffee from a gourd as another woman looks on. Their dark black skin in indicative of the harshness of the sun.

We talked about how the government forbids this practice (with pressure from the global community) and will jail anyone caught performing this cutting ritual. But one of the tribesmen said that the law won’t change anything. He said that the custom is very old and that everyone in the tribe accepts it as a necessary practice. At the same time he admitted that the need for Dimi may stop as more young people are educated.

Know that this cultural tradition is supported by the tribal men, but it is supported and performed by the women! They see this as a way of keeping the women from shaming their families by having affairs outside of their marriage. If a young teen refuses the “ceremony,” they won’t be allowed to marry or have children, and they will be ostracized from their tribe — because they will be seen as nothing more than a wild animal.

I started asking Fitsum a million questions. He answered with matter-a-fact answers, in the same tone as if we were talking about the weather. My female western mind was truly unable to comprehend the reasoning. The pain. That’s when I really started noticing with acute awareness the women’s expressionless faces and blank stares — the I-checked-out-of-my-body blank stare.

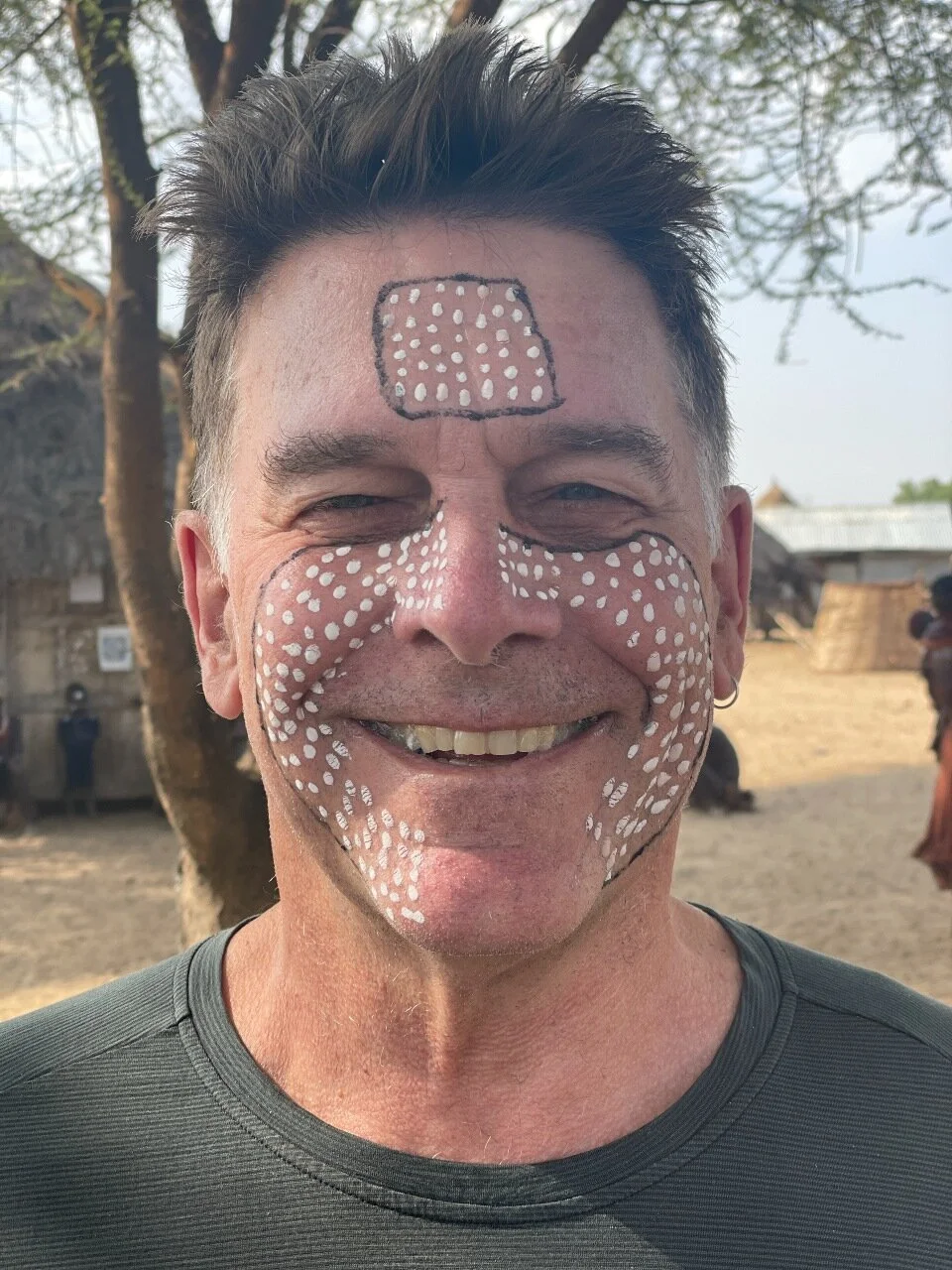

THE KARO

We arrived here early the next morning. I was getting tired — emotionally and physically. A new tribe or two every day. How many more do we need to see?

But the Karo tribe was special. Not only was the village beautiful — being perched above a bend in the Omo River, but it was greener and shadier than most. And the people were truly unique and interesting.

They are the first tribe we visited that really embraced body painting. I thought they were playing dress-up for our visit, but this is their norm.

They use ground limestone and water, or river mud and cow manure, to bless their bodies — the substance also acts as sunscreen.

They asked us to join them and, of course, how could we say no? With the limestone mix, that is.

This was where we met Arsema (the little girl who latched on to me and wouldn’t let go) and where I learned about Mingi children — children deemed “cursed” by the elders and either killed or left to die in the bush.

Unblessed children. Children out of wedlock. Malformed babies. Twins, and babies who’s top teeth break through their gums before the bottom ones do — this criteria determines if a child is Mingi!

Elders believe that a cursed child will bring drought and famine to the area, so they choose to eliminate the child rather than to suffer the consequences.

And to think that this has been going on for thousands of years.

This is becoming all too much for me. Am I taking it too personally? I’m trying not to judge, but it’s not working.

Then I found a bright light….

Nadin Hailo. Operation Smile repaired her cleft palette when she was a baby.

Meet Nadin.

She was a Mingi child.

Born with a cleft palette and one eye. And her mother died during her birth.

If you’re wondering if one person can make a difference in this crazy world, as I did, here’s a man who absolutely did. Lale Labuko. Born into this Karo tribe. He grew up with the notion that Mingi was wrong and must be changed. And he’s doing just that. We didn’t get to meet him but Fitsum shared his story.

Lale and his wife founded My Omo Child Orphanage. They save Mingi children. They save them, give them a good home, food, clothing, education and love.

Nadin was a saved Mingi child — the direct result of Lale’s work!

I was curious to know more about Mingi, Lale’s work and what could one person like me do to help, so I watched Omo Child: The River and The Bush and Lale’s TedX Talk. Both were fascinating resources, and they gave me hope and an outlet to help fund their work.

— If you’d like to know more about The Omo Child Orphanage, you can read about it here —

MORNING SURPRISE

So, we’re into this journey 10 days so far. I’m ragged and worn slick and I’m not sleeping well, but I feel like I need to journey on.

Fitsum and Israel say they have a special treat for us. They want us up and out the door by 5 a.m.

Here we go again.

So the next morning we drug ourselves out of bed in the dark and climbed into the truck. We had a long drive ahead of us.

We drive for what seems like an hour up a steep hill, and then pull over and park. The boys get out, drag stuff out of the back and set up this amazing picnic breakfast — hot coffee included. How sweet is that?

Scott and I sat and ate in silence — watching the sunrise over the distant mountain.

Then, boys being boys, they climb on top for this photo op.

THE MURSI

The Mursi’s are one of Ethiopia’s better known tribes. The women are famous for their decorative lip and earlobe plates that are cut and stretched into their skin, and a unique cutting technique that resembles a raised tattoo.

In a sign that the old customs are changing, we were told that the younger generation is shying away from lip stretching and prefers to only decorate their earlobes.

The Mursi tribe is nomadic. They don’t have a permanent village. In fact, they live in a national park — one that the government allows them to inhabit. But looking around we noticed was how trashy it all was. There wasn’t a sense of pride or permanence in their surroundings.

MY FINAL STRAW

Again, it was hot. The flies were intense. It was dirty. And I kept thinking that the tribe members posing for us were only doing it for the money.

It all seemed wrong.

I found myself wanting to leave. Immediately. I had hit a wall. Too many tribes in too few days. Between the weird food, the hot, sleepless nights and way too much emotional input to process without some down time, let’s just say, I snapped.

My head and stomach hurt. I thought I was going to throw up. I couldn’t breathe. I was on the verge of a panic attack. I told Scott I was going to wait in the truck and for them to finish their visit. But he knows me well enough. When I say I’m done, I mean it. He pulled Fitsum aside and before I knew it we were out of there. Whisked away. Headed back to the lodge.

I cried the entire way.

All I could do was focus on getting out of Ethiopia. This place wasn’t for me. I thought about hiring a driver and heading to the nearest airport. Get me out of here!

Everyone gave me space that day. I think Scott was afraid of hearing what was on my mind. I rested for a few hours. Took a shower and laid down to rest. I started feeling better. I talked to Scott. He told me that we were leaving and heading north and it would be much different there.

And so we did.

AMAZING CONNECTIONS

Sisay Simon

THIS YOUNG MAN…

When we visited his tribe, Sisay Simon, was one of the first young men we met.

While visiting the Dassench Tribe, one of the mothers brought us her baby and we quickly noticed his eyes were matted and swollen shut. Scott asked what was wrong and could he help.

Sisay, an 8th grader at the local school said he’d be happy to take the mother and child to the local doctor but that he needed money to pay for medicine. Scott gave him some cash and asked him to report back. Later that day, Sisay texted pictures of the child at the doctor’s office, along with photos of the prescribed medicines.

He and Scott had a nice connection and they continue to stay in touch. Scott has also decided to help him financially so he can progress in school.

AND THIS ONE…

Ayela Gade

We met Ayele Gade at the local market near Omorate.

He very quietly stood beside me that day and said, “I’m studying English, and I’m wondering if you could help me buy an English book?” In a place where almost no one speaks English, I was beyond impressed and very quickly said “Yes!”

Ayele is an 8th grader and self-studies English. He really wants to stay in school.

We continue to stay in touch via WhatsApp and I have provided some funds for Ayele’s books, food and clothing so that he can continue his education.

AND FINALLY…

Our guide. Fitsum Ashebir.

Fitsum’s story shook me. As travel guides go (and we’ve had a lot of them), he’s a pretty damn fine guide. The tribes all know, love and trust him, and they welcome anyone he brings into their world.

Fitsum Ashebir

But there’s another layer to Fitsum that took us a couple of weeks to uncover. One that had to be coaxed out of him. He grew up in the Omo Valley and was born and raised in these eucalyptus mud huts. He’s a member of the Hamer tribe.

Fitsum is an Omo Child.

He didn’t talk a lot about his personal experiences, however, when he told tribal stories, he seemed to talk with such a depth of knowledge that I wondered how he memorized all of the details. He didn’t. He lived them.

Fitsum’s success story began many years ago when he walked up to a Frenchman visiting a local market and held his hand. This man, who with no real cause, saw something in Fitsum he liked and decided to fund Fitsum’s schooling.

Fast forward, twenty years or so, Fitsum now has a university degree in public health, and owns and operates Omo Valley Tours.

Fitsum is educated and successful and, because of the kindness of this one stranger, he now owns a business and several touring trucks and employs staff.

This opportunity isn’t available to so many of the Omo Valley children.

Fitsum and the Frenchman kept in touch over the years until the man’s death just a few years ago.

When I asked Fitsum if his parents taught him to hold hands with strangers, he said no one told him, he just knew that this was a way to connect.

OUR GRATITUDE

Many thanks to Fitsum and Israel for this part of our journey. Believe me when I say there’s a stark difference between being a tourist who throws money at children for some Instagrammable photo ops and being allowed into these tribes to hear their intimate details as a trusted friend. These guys were our non-judgmental liaisons and tribal gurus into a world of non-sugar-coated tribal living.

Isreal Legesse and Fitsum Ashebir

OUR ACCOMMODATIONS

IN KONSO

We had some truly unique accommodations along the way.

The Kanta Lodge. Similar to local huts, but with indoor plumbing.

IN TURMI

As some of their only guests, we were treated like royalty.

As we got deeper into the valley, we settled into the lovely but basic Buska Lodge.

With nighttime temps in the 90s and electricity produced only by generators (which were turned off at 10 p.m. along with the wifi), we spent a few sleepless nights in our mosquito-netted beds hoping for a breeze.

IN JINKA

Eco Omo Lodge

Also their only guests, we opted for “luxury” accommodations — which meant we weren’t sleeping in their tents. We had running water, mosquito netting and a fan! And the electricity ran all night.

Their restaurant catered to our every need and the owner allowed us behind the bar to fix our own drinks. Just what the doctor ordered.

WHAT TO DO WITH THESE EXPERIENCES?

I ask myself this question everyday.

It’s been hard to put into words all of my feelings. The judgmental feminist in me is extremely angry at these women for putting up with this treatment for so long, and the other side of me feels absolutely helpless in not knowing what to do with the information.

And now that I know about all of these sweet and hopeful faces, it’s hard to sleep knowing they will soon face the same harsh realities as their parents.

Writing this blog has been a huge help in organizing my thoughts and feelings. That said, there’s so much I left unsaid.

NEXT STOP?

Northern Ethiopia